Remember their Stories

Wednesday, April 11, 2018

Sunday, January 5, 2014

On November 6, 2013, my fiance, his parents and I visited my Buba and Ziedi in Florida. Over a hearty brunch, truly enough to feed an army, with blintzes, bagels, whitefish salad, lox, and coffee, Buba recalled stories of their time in Israel after the war. She brought out her Poesiealbums--which are essentially poetry albums, a collection of autographs, dedications, and drawings from close friends, relatives, and acquaintances. The albums were over 60 years old with some entries dating back to 1944. Due to the delicate nature, I decided to borrow both books in order to scan and preserve. See a few of the scans below.

Next, I plan to mail the scans to Buba in order for her to translate the Yiddish, French, and German excerpts.

Friday, August 19, 2011

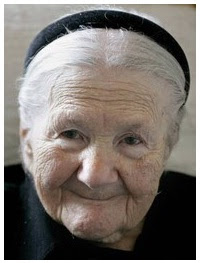

Remembering Irena Sendler [1910-2008]

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

Exhibit: Radical Departures - The Modernist Experiment

Monday, July 18, 2011

WSJ Reviews Eisenman's Berlin Memorial

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

It's not all about sex...

Last week, I was invited to the Center for Jewish History in Union Square for an evening of music and discussion organized by the Leo Baeck Institute and Germany Close Up.

The guest of honor for the event was none other than Dr. Ruth Westheimer, famous of her candid sense of humor about all things related to sex. I've heard Dr. Ruth speak before and have always found her brilliantly entertaining and down-to-earth. What I didn't know about her, is that she is a Holocaust survivor. Born Karola Ruth Siegel in Wiesenfeld, Germany, she was the only child to Orthodox Jewish parents. She lived with her parents and grandmother in Frankfurt, Germany until January 1939, when she was sent to Switzerland after her father was taken by the Nazis. Dr. Ruth explained to us that she was one of 10,000 children selected to be sent to neighboring countries for an intended period of six months during the beginning of the war. Fortunately, she was sent to an orphanage in Switzerland, where she ultimately lived for the next six years. If she had been sent to France, she would have had no chance of surviving the war.

At age 16, Dr. Ruth went to Israel where she was trained as a sniper as a member of the Haganah. Injured after only a short period of time, she moved to Paris, where she studied psychology at the Sorbonne. She immigrated to the U.S. in 1956 when she obtained her Masters degree in Sociology from the New School and her Ph.D. in Education from Columbia University. She got her start in human sexuality studying under Dr. Helen Singer Kaplan at New York Hospital Cornell University Medical Center. The rest, so to speak, is history.

Dr. Ruth, truly a pioneer in "sexual literacy," has authored 22 books, and aired on radio and television. She recounted a story when Diane Sawyer interviewed her for Good Morning America in her apartment near the Palisades. Diane Sawyer asked Dr. Ruth's husband, Fred, "So, are you benefiting from your wife's studies?" To which, Fred quickly replied, "Let's just say, the shoemaker's kids don't have any shoes." Dr. Ruth let out a little chuckle after telling the story. Her warm, sincere, and slightly off-beat personality engaged the crowd that night, including myself—having learned that Dr. Ruth escaped the perils of the Holocaust made me admire her even more. And at the end, she encouraged all of us and our generation to learn and achieve for our parents and our grandparents.

---

The Leo Baech Institute is devoted to studying the history of German-speaking Jewry from its origins to its tragic destruction by the Nazis and to preserving its culture. To learn more about the Leo Baeck Institute, go to http://www.lbi.org/. The Institute hosts various lectures and exhibitions in Washington, DC and New York, NY.

Friday, May 27, 2011

Message from Dana Weinstein at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

But in a century already marked by genocide and an alarming rise in hatred, this effort grows more challenging—and more urgent—with each passing day.

Today's younger generation holds the key to carrying these lessons forward, but a survey found that 20 percent of American high school students could not identify Hitler or name the countries the United States fought in World War II. Our Museum remains an essential source of knowledge to educate new generations about the Holocaust and ensure its horrors are never repeated.

But we can't do it alone. Please consider contributing a special gift to the Museum today:

http://act.ushmm.org/your-gift

Your gift will help educate young people the world over about Holocaust history and the dangers of unchecked hate. In doing so, you honor the victims of the Holocaust and turn their memory into action.

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

A moment of pause

Only take heed, and keep your soul diligently, lest you forget the things which your eyes have seen, and lest they depart from your heart all the days of your life; make them known to your children and your children's children.

- Deuteronomy 4:9

I am not one that usually quotes the Tanakh, but this particular passage struck a cord with me. It is not an easy thing to discuss painful memories, let alone to approach the subject of such sadness with someone you love. And even as I was compiling material for this blog, I was reluctant to share it with my Buba and Ziedi until I had a good grasp on its ultimate purpose. When I was in Florida visiting last Fall I sat with my Ziedi to show him the blog and explain what I had in mind. I hoped that I had accurately captured and depicted his story in a respectful, straightforward manner. My intention was not to shock readers with horrific, gruesome details, but to shape the life that my Ziedi had before, during, and after the war. He read my blog, nodding throughout and at the end paused, focusing on the computer screen.

'Did you know I had eight brothers and sisters?' he asked me, his eyes glistening.

'I had no idea,' I replied. It's true, it was never mentioned in his 1993 interview recording, nor when I was growing up.

He took a piece of paper and proceeded to write the names of his siblings in the order of their birth. Looking over his shoulder as he wrote, I felt extremely grateful—grateful for the fact that my Ziedi was still alive and healthy, that I would be able to perpetuate his story, and that we had shared this moment together. Without this blog, I know that that piece of my Ziedi's history would have been lost. Now I have the names of all of his family members, information I look forward to sharing with my family's future generations.

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Currently Reading...

Women who held their ground

Of the dozens of Jewish memorials scattered throughout Berlin, my favorite are a series of statues of women and children in embrace. The memorial recognizes the nearly 6,000 unarmed and determined women in 1943 who defied the Nazi's and won. To me, these statues send a powerful message and represent courage and triumph during a time that was otherwise marked my strife and defeat.

The story holds that the Nazis wanted to clear out the last remaining 6,000 Jews in Berlin. About 2,000 mostly male Jews were rounded up to be sent to death camps. These men were husbands of non-Jewish women. The Nazi's separated these men from the rest of the Jews and had hoped that the women would believe that the men were just being sent to another force labor camp. However the women found out about the plans to send them to death camps and also discovered that they were being kept in a Jewish welfare center. Many of the women began going to the Jewish welfare center and asking for items from their husbands to confirm that they were being held there. More and more women and children of the men began gathering where they were being held. By the second day there were more than 600 people keeping vigil outside the building, and chanting for the release of their husbands. On the third day SS troops were ordered to fire warning shots. The women scattered but returned and held their ground convinced that the SS officers would not fire at them because of their German heritage.

The Nazi's own ideals also helped the women's cause. Nazi's believed that women were intellectually unable to be involved in political action. Nazi's also proclaimed itself as the protector of motherhood, so arresting or injuring any of the women would have smudged their image to other Germans. Soon protestors who were not related to the prisoners also joined in and the group often reached over a thousand. The leader of the SS in the area saw no other choice than to let the prisoners go. Thirty five men who had already been sent to Auschwitz were sent back to Berlin. Eventually all the men were released and nearly all of them survived the war.

The building where the men were held was destroyed during the end of the war, but today a memorial stands in a nearby park which commemorates the women who were willing to stand up to the Nazis. The inscription on the back of the memorial says, "The strength of civil disobedience, the vigor of love overcomes the violence of dictatorship; Give us our men back; Women were standing here, defeating death; Jewish men were free."

The day that the men were released was the day that love conquered one of the most brutal regimes known to mankind. A few thousand women without arms were able to save 2,000 Jews from certain death.

Monday, April 11, 2011

Detached City

Sunday, March 20, 2011

Bleak Skies

Sachsenhausen concentration camp, just outside of Berlin. I wondered

if there was any other weather that would've been more appropriate for

what we were about to see. Sachsenhausen was built in 1936, one of the

earliest constructed camps in Germany, it housed 200,000 prisoners

until it was liberated April 22, 1945.

Our guide explained to us that while the camp was liberated in 1945,

it was quickly in use again until 1961, occupying German perpetrators,

Soviet spies, and others awaiting trials for their crimes. While death

presumed, it was out of starvation and old age, not the

individually-executed and meticulously planned extermination that was

performed years earlier against the Jews, Gypsies, and homosexuals.

As we walked the grounds, little remained of the original structures.

The camp was first bombed by East German policemen in the 1980s and

then again in 1992 by Neo Nazis from surrounding towns. Little was

done to rebuild the effects of either arson-- Bunker 38, which housed

over 800 Jews at any one time, was half destroyed by fire and what

remained was marred by singed wood and peeling paint.

Our guide gathered us where daily roll call occurred some 60 odd years

earlier. He continued to provide us with a factual narration of the

camp's history. The still air was biting and while dressed

appropriately for the cold, I felt chills up my spine. My hands were

clenched and dug deeply into my pockets, my scarf rewrapped to cover

my ears, and yet I could not get warm. How could I complain knowing

very well that my Ziedi stood in worse conditions wearing nothing but

thin, paper cloth pajamas? Was this the point? To replicate the

feeling of sheer helplessness? We were outside for an extended period,

standing still and I couldn't fight the cold anymore. I quietly

separated from the group to return to the memorial museum and quickly

became disoriented. I walked along the rubbled paths and was met by a

dead end. There was a way out for me, but not for so many others.

I turned around and walked in the other direction.

--

Jess.

Saturday, March 19, 2011

Stumbling Stones

The first line: Hier Wonte means Here Lived. The next line is the name of the individual who died, then the year he or she was deported, where, and lastly the year the person was murdered.

These mini plaques are slightly raised in order for pedestrians to "stumble" and look down. These particular stones were outside of trendy boutiques, which once housed this family of five. It certainly is a paradox...Berlin is full of contrasting themes, which have made me "stumble" and pause.

Empty Spaces

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

The Memorial

The Memorial of the Murdered Jews of Europe opened May 10, 2005, having marked 60 years since the end of the World War II. Located in central Berlin, the Memorial is a field of 2,700 concrete slabs near the Brandenburg Gate, designed by Jewish architect, Peter Eisenman. Eisenman constructed tilting featureless stones, each unique in shape and size, in an undulating labyrinth that spans a 204,000+ square foot field. While other memorials often include plaques or inscriptions, Eisenman said "[he] fought to keep names off the stones, because having names on them would turn it into a graveyard."

The Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben, visited the Memorial and wrote that "[it] does two things and that there are two kinds of memory. There is the immemorable, that which is unable to be portrayed in memory in any form. The Memorial comes close to the immemorable, the possibility of something that you cannot memorialize because it is so horrific or extensive that anything representational would reduce its own significance. The Memorial also allows for the other part of memory, the archival. The field is the immemorable, and the exhibition below is the archival memory. The Memorial does as no other memorial has, which is to bring these two together simultaneously."

As much as I am looking forward to the program in Germany, I know that the Holocaust-related portions of the itinerary will be physically and mentally confronting. Unfortunately, there is no amount of preparation that could possibly steel me from the affects and emotions that will stem from seeing these memorials up close, in the country where it all started. Nor can I predict how I will categorize or memorilize these events in my mind, but only hope that it will provide me with a better, more concrete recognition of what occurred.

|

| The Holocaust Memorial of the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, Germany |

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Currently Reading...

|

| Felice with her grandfather, Murray |

Excerpt from the Book

“Feigela,” Papa’s eyes were moist as he spoke my Yiddish name. “I want you should write my story.” He was looking out a glassed-in porch, four stories above a deeply green manicured lawn; a serene blue river cutting precise S-shapes throughout. Animating this Disney-perfect shoreline were dozens of bright white herons, while common hawks flew overhead. We were sitting on the terrace in one of several identical condominiums inside Papa’s gated community in Boca Raton, Florida.

“Feigela,” Papa’s eyes were moist as he spoke my Yiddish name. “I want you should write my story.” He was looking out a glassed-in porch, four stories above a deeply green manicured lawn; a serene blue river cutting precise S-shapes throughout. Animating this Disney-perfect shoreline were dozens of bright white herons, while common hawks flew overhead. We were sitting on the terrace in one of several identical condominiums inside Papa’s gated community in Boca Raton, Florida.“But it’s not just in the camps I had to survive,” Papa said. “All my life I’ve come up against roadblocks and had to find ways to push through. I lived my life always with my kids in mind. I want they should know my story so that they can learn to survive, too. People should know,” Papa had decided, “so that it doesn’t happen again. I lost most of my family - parents, siblings, cousins, so many killed. I suffered conditions you shouldn’t know from. But I never complained.” His eyes grew moist. “I’m just an ordinary man who lived his life.”

I took out a notebook.

Here is what Papa told me.

Sunday, February 20, 2011

Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead

Sunday, December 5, 2010

3GNY Support

Current Exhibitions at The Jewish Museum

In celebration of Hanukkah, my friend and I visited The Jewish Museum today on the Upper East Side. Two exhibits worthy of seeing are:

A Hanukkah Project: Daniel Libeskind's Line of Fire - The installation displays a wide range of modern to traditional menorahs, totaling 40 Hanukkah lamps from all over the world. Below is a Hanukkah lamp by David Heinz Gumbel, Heilbronn, Germany, early 1930s, silver, hand-worked.

– This exhibition features works by seven artists inspired by Hanukkah. My favorite, pictured below, a creative and fun interpretation of old traditions by Lyn Godley, titled Miracle (2004), will surely bring a smile to your face. Backlit digital imagery is illuminated one 'candle' at a time as the LED and flicker bulbs light up from right to left. Other artists’ works include: Alice Aycock's Greased Lightning, a kinetic, steel sculpture with three rotating driedels, and Matthew McCashin's Being the Light, another bright wall-mounted menorah with porcelain light fixtures and metal electrical conduit.

Seven Artists

Both exhibits run through January 30, 2011. Saturdays admission is free. For museum hours and more information, go to http://www.thejewishmuseum.org/index.php.

Friday, October 15, 2010

My Ziedi's story was videotaped by the Holocaust Research Center in Buffalo, NY on March 29, 1993. I've transcribed his interview below, these are his words.

Part One:

I was born March 3, 1925 in Bilgoraj, Poland. I was the third born, and had three brothers and five sisters. My father was a baker and owned a bakery. Considering the situation in Poland at the time, I had a good childhood. I was never hungry, I was dressed well, went to a good school, and lived comfortably. We had a nice extended family with many cousins, aunts, and uncles. My grandfather was a prominent businessman, who worked for a Jewish bank..

The Germans arrived in 1939. Our town was surrounded by forests and there was a forest ranger, who turned out to be a German spy. The Polish army had set up several hiding places in the forest and caught the forest ranger taking photos of their lairs. The Polish officers shot him. The very next day, our town was in flames. There must have been other spies because from all four sides our town was burning. Fortunately, there was a well in our backyard and a pump into our family’s bakery. Town members started gathering water to put out the fire. It saved our family and our bakery.

That September the war started. The Germans came into Bilgoraj and chased everyone out of town. Shortly thereafter, a few German officers came into the bakery and called out, ‘Who is the baker?’ My father stepped forward and said ‘I am the baker. But there’s no yeast or flour.’ One German replied, ‘We’ll give you what you need.’

The Germans paid my family for the bread. Two weeks later though, the Germans came in and said they were leaving and that the Russians were coming. Our town was right in the middle of a German-Russian disagreement. The Russians came in and we did the same for the Russians. We baked them bread. Then two weeks later, the Russians said that they were leaving and that the Germans were coming back, but said they were no good, so whoever wanted to leave town, the Russians offered transports to leave. My aunt and uncle’s family house had burnt down, so for them it was a logical decision. But my father said that we still have a home and a bakery, maybe the Germans won’t be so bad, so we’ll stay. My aunt and uncle and their six children went deep into Russia. In 1945 when they returned to Bilgoraj there was nothing left. In 1948, they immigrated to the U.S, and still reside in New York to this day.

After the Germans came back, they took the bakery away from our family because they explained that Jews can not own any businesses. They gave the bakery to another Polish family, whose bakery had burned down in the fire. The Polish baker had worked for our family, so he offered my father and older brother a job – my older brother went to work there, so fortunately there was bread for us, we had food. But my father, he started baking bread on the black market from our kitchen.

When I was 15, I began working for a roofer and we worked for the Germans building a field hospital. We nailed down the tar paper as fast as we could—the Germans made things quickly and cheaply, so they used the tar paper for the roof, but the cold winters caused the nails to pop up. So every summer, we came back and nailed down the nails again and re-tarred the roofs.

My family was considered fortunate. We had beans, potatoes; we made noodles, but didn’t have much meat. We had food to supplement our bread. The bread was made with sawdust, which was mixed right into the flour. And we survived three deportations. Before the Nazis, there were 4,000 people, while it was a small town, it was a Jewish town. There was a Jewish mayor. My grandfather was a ludvik, he was on the city council. And the fact that we worked, we were productive, it helped save us from the initial deportations. We were aware of the concentration camps. In 1941, there was a very well-known Polish man who was arrested and a few weeks later a little box of ashes was sent to his family.

The fact was we were not in hiding during the first or second deportations. Where would we hide? There was no one to take us in and there was nowhere to hide. Then, my mother, may she rest in peace, my five sisters and my brother went into hiding before the third deportation. The Germans couldn’t find them. There was an old house with a basement; the entrance to the basement was from the outside, which was covered up with dirt and couldn’t be seen. The house had a wooden floor and few boards were taken out so that they could hide under the boards.

At the time, I was in the Lodz ghetto, I went to the Polish baker who we knew and I bought bread from him. Another boy hiding in the basement with my family would meet me in the ghetto at night and pick up the bread. My family was there for six weeks. They couldn’t go to the bathroom during the day, so they had to go in pails. But at night they went out to the outhouse. Then when it began to snow, the Germans saw the footprints and discovered my family hiding. The Germans took them outside and shot them. The boy, my friend who was also in hiding, was in the outhouse at the time and saw what happened. The next day, he came to the ghetto and told me the whole story.

Part Two:

On January 8, 1943, the ghetto was liquidated. They took all the men out and put them in jail. The women and children were shot right there in the ghetto. From jail, the Germans took us to SS barracks located near Zhamish. At these barracks, the SS learned how to ride horses, so we built stables for their horses. I continued to work as a roofer. Each day the local farmers brought stones and wood for the building supplies and they used to bring bread to sell. Fortunately, I had money from the ghetto, so I was able to buy bread and eat. The conditions in the camp were not very good, we slept in the stables on the floor with a little bit of straw, even in the winter. There was one wood burning stove in the middle of the stables. We had a little soup everyday and the extra bread we purchased from the Poles. There was no luxury, but I could survive on what I had.

One day, a German went out and shot a dog and brought it to the cook. He instructed the cook to serve it to us. He said, ‘If you tell any of the Jews what you’re cooking, tomorrow we’ll cook and serve you. At dinner, the officers sat us down at the table and served us portions of the meat. We ate it hungrily. Then a few of the Germans came in with cameras and began taking pictures. ‘Do you know what you’re eating,’ they asked. ‘No you don’t? Does it taste good?’ We replied, ‘Of course it tastes good.’ That made the Germans laugh, and they said ‘Well, it’s dog. You’re eating dog.’ We didn’t care, it was good and frankly, we were starving. So the joke was on them. When you are hungry, you will eat anything.

By then the work on the stables was finishing. There were 80 of us and one-fourth had to be liquidated. The Germans simply went around pointing until there were 20 Jews and the Germans shot and killed them by the stables. After, they liquidated the whole camp by putting us on trucks to Majdanek, another concentration camp where conditions were bad.

By the middle of 1943, around May or June, the Germans were running out of workers. There was a need for laborers, so the killing subsided. When we arrived at Majdanek we were forced to remove our clothes. There was a German there to shave off all our hair, all over our bodies. Once done, there was another German who looked us over. If someone looked sick they went one way, if they looked healthy you went another. The ones in the sick line were killed. The healthy ones were sent to the showers and we were sprayed with a very strong smelling solution, probably chlorine. We were given striped pants and a jacket, made out of some sort of very thin paper. There was no underwear, no socks, nothing other than the clothes and clogs we were given. I was at Majdanek for eight weeks. It was bad, in the morning we were given a little burnt coffee and during the day a little soup with a piece of bread. The bread was baked with all sawdust; there was no flour at this point. And there were thousands of prisoners per barrack; we were all cramped in together.

One day, the Germans came in and said ‘Whoever knows how to work with sheet metal, step outside.’ So I stepped out, I knew how to work with metals from my time as a roofer. All of us that stepped out were put into an empty barrack. The next morning, we were put on a train, more like cattle carts, given blotworst, a piece of bread and cheese. We arrived in Skarżysko Kamienna, Poland, where there was an ammunition factory that made bullets and grenades. The Germans did not have enough brass or copper to make bullets, so they used steel. I was assigned to work in the “laundry.”

In the laundry, I cleaned the rust off of thimbles. There was a machine that had a strong acidic solution that cleaned off the rust. Every day, I was inhaling this very hot, strong smelling solution. I put the thimbles into this machine to clean them. After, the thimbles went into cold water, then hot water with soap, lime, then this cycle was repeated. Once dried, they came out twice the size and eventually became bullets. The factory had to make a million bullets a shift, 12 hours a shift.

During the day, we were given soup. The Germans for some reason liked me, and if there was any soup or milk leftover, I would get some. One night when I didn’t have much to do, I went in between the machines and took a nap. Another German officer came over with a hose and sprayed me with cold water. My boss yelled to the other German, ‘What are you doing?’

‘The swine is sleeping can you believe it,’ the other officer said.

‘Leave him alone, he did his job, he is fine where he is.’ My German boss protected me, I was lucky.

Sometimes there was extra clothing from dead prisoners. I stood in line and got a nice winter coat. A Polish civilian approached me and asked to buy my coat. I said ‘Well, if you have another coat to bring to me, and I’ll sell you this one.’ The man brought me his old winter coat and gave me 600 lutus. Considering for only 60 lutus, I could purchase 2 kilos f bread, I thought this was a good deal. So I sold the coat for bread money. My friend in the camps, we were partners, whatever he got was ours, whatever I got was ours. I worked the night shift and my friend was the day shift.

At this point, it was January 19, 1945. We kept a calendar with us to keep track of the days. The Germans wanted to run away, they were losing the war. That evening, the night shift workers, including myself, were put on another train and sent to Buchenwald. Two days later, January 21, 1945, the day shift workers, including my friend, were liberated by the Hungarians. My friend was free, but I continued work in the labor camps.

At Buchenwald, I worked in an airplane factory for small fighter planes. I had to shoot rivets into the planes; each had to be done exactly right, perfectly. If it was wrong, it had to be drilled out and redone. I had an air gun, but the kick-back from the gun was so powerful. I didn’t think I would be able to work with it. But ultimately, the pressure was on my boss, who was in charge of us. He taught me how to use the air gun and gave me extra bread and soup. I worked there for about three and a half months.

Then, one night, my boss came into the barracks and yanked me out. Those who worked stood in the factory, those in the barracks were taken out, half were missing, and I had no idea what happened to them. We heard canons and rifle shooting in the distance. We were forced to march, about five to six kilometers, towards Magdeburg. While we were walking, there were street fights going on, so we turned around to start walking back to the barracks. At night, I saw people starting to run away, even the SS. The SS had civilian clothes under their uniforms. I decided to also run away, so I lay down quietly and rolled into a ditch. When I thought it was clear, I went into the field and pulled away a bale of hay and snuck inside. I fell asleep and the next morning, I heard people talking. I realized that we were all hiding in the bale of hay, there were dozens of us. We lay there till noon then noticed black people driving trucks. We knew they weren’t Germans, they had to be Americans. From the trucks, the Soldiers were throwing chocolate. Truthfully, I wanted bread, but I ate the chocolate.

It was April 12, 1945. When I was liberated, it wasn’t the happiest day of my life. I wept. What was I going to do? Where was I going to go?

I remember so clearly the day I left my family to go to the Lodz ghetto. My mother took me to the gate and she turned to me and said, ‘Sam, you go, maybe you’ll survive.’ I did what I had to do.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

We all grow up using special, and often affectionate, nicknames for our grandparents-- Nanna and Pop Pop, Grandma and Grandpa, and in my case something slightly more unique-- Buba (Boo-bah), which is the Hebrew word for doll, and Ziedi (Zay-dee), which is the Yiddish word for grandfather.

We all grow up using special, and often affectionate, nicknames for our grandparents-- Nanna and Pop Pop, Grandma and Grandpa, and in my case something slightly more unique-- Buba (Boo-bah), which is the Hebrew word for doll, and Ziedi (Zay-dee), which is the Yiddish word for grandfather.

To appreciate my Ziedi’s insistence on good, hearty food for every meal is to know his past. And as he gets older, I realize how increasingly important it is to understand his story, so in addition to his recipes, I can pass down his legacy.

I am the granddaughter of Samuel Sysman, a Holocaust survivor, and I intend to tell his story through this blog. Please share your stories and questions with me, I look forward to being inspired.